|

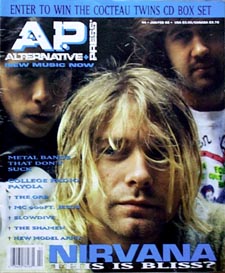

This Is Bliss?

Alternative Press, Jan-Feb 1992

If only there were a way for Nirvana to be a celebrated rock group and veritable unknowns at the same time. Giving interviews, being recognized, signing autographs - you name it, Nirvana hates it. But when the latest punk-rock heroes from the Seattle suburbs grumble about being successful major-label commodities, it's tough to sympathize. After all, they willfully left the relative obscurity offered by independent record company Sub Pop to sign a two-record deal, with Geffen in 1990. It's like moving from a small town to Los Angeles and complaining about the smog - it sort of goes with the territory. So the question remains: if being popular is so offensive to Nirvana, why court popularity?

By Susan Rees |

|

|

Just getting through this interview proved too much for the press-weary band. Spread out about as far as three people can spread out in one small New York City hotel room, they tried to be responsive, but Sunday afternoon weighed heavily on them. Instead, bassist Chris Novoselic, who did offer a Beck's and some Pepperidge Farm cookies, showed more interest in watching television, drummer David Grohl was polite but didn't have much to say and vocalist/guitarist/songwriter Kurt Cobain - who sat at a desk facing a window - spent the greater part of his energy eating lunch and holding his very hungover head in his hands. Apologetically, they followed up with phone interviews. To follow up their 1989 Sub Pop debut, Bleach, Nirvana left behind the heftier grunge that they helped popularize for pure, punky pop. And if their sound can be described the way Cobain puts it - as the Knack and the Bay City Rollers being molested by Black Flag and Black Sabbath - then Bleach was heavy on the Sabbath while Nevermind leans more toward the Knack. Cobain discounts the progression. "I really don't feel there's much of a difference between the Bleach album and this album besides the fact that we don't bend our strings as much," Cobain tries to assert while slumping over his food. "I think we've always been a pop band." Despite what he may think, the 24-year-old's songwriting has come a long way these past two years. Though the songs on Bleach have an immature and sloppy charm, cheese-metal dinosaur Ted Nugent could have written some of the guitar riffs. On Nevermind, however, the shorter, more infectious verses, choruses and bridges are structured to wrap around one another and recur, making each song round, complete and satisfying. "To me, that's what pop music means," says Cobain. "Something in repetition." Cobain likes the songs on Nevermind better than those on Bleach; perhaps it's because these days he uses different emotions from which to write. Using hatred, he felt, imparted a certain gloominess to the songs on Bleach. "I don't hate anything anymore; I did when we were writing Bleach," he says, though he won't get more specific. "Now I think it's turned into frustration. And confusion." Better sound quality also makes Nevermind more accessible than their first album. Bleach's 1970s-era muddiness came courtesy of producer Jack Endino and a $6oo studio tab. "With the new album we tried to get more of a studio sound," says Cobain. "I felt it was the best way to put these songs across." Butch Vig supplied his classic larger-than-live production - the type he's demonstrated on numerous other recordings, including the Smashing Pumpkins' debut - and finally carried Nirvana straight into the'90s, right where they belong. In the ' 90s, unfortunately, the rock media regularly tries to impose greater significance on popular music than the artists may have begun with. Think of a journalist elevating Madonna's masturbatory crotchgrabbing to a statement on women's rights, and you're thinking of someone who's stretching for something to talk about. Cobain may have qualms about his lyrics being the object of such invention, but in the end he goes along with it. "We have to make up an excuse for what I've written later on when someone asks me. The majority of my lyrics are just lines from poems I've written," says Cobain, referring to the poetry he's written since junior high school. The process is "therapy" for him, so he rarely lets anyone see it - unless it crops up in songs. "It's mainly just words, words that hopefully paint a picture," he says, stressing that he means that sarcastically. The pictures painted by the lyrics on Nevermind are sometimes ugly. The song "Polly," for instance, directly opposes a straightforward acoustic ballad with a creepy lyric written from the perspective of a rapist. Let me take a ride "There have been a few complaints from people who say it glamorizes rape," says Cobain, "but I just tried to put a different twist to it. It's definitely not a pro-rape song." |

|

|

< PAGE 2 > Main Page | Interviews |